Whether you’re a criminal investigator or a chief, it is consistently interesting to take on another case. The last time Rian Johnson made a spin-off (2017’s The Last Jedi), he almost broke the web, or if nothing else the side of it that likes to squabble over Star Wars; the last time respectable man criminal investigator Benoit Blanc tackled a case (in 2019’s Blades Out, Johnson’s part love letter to, part disruption of the Agatha Christie murder-secret class), he almost fell into a figurative donut opening.

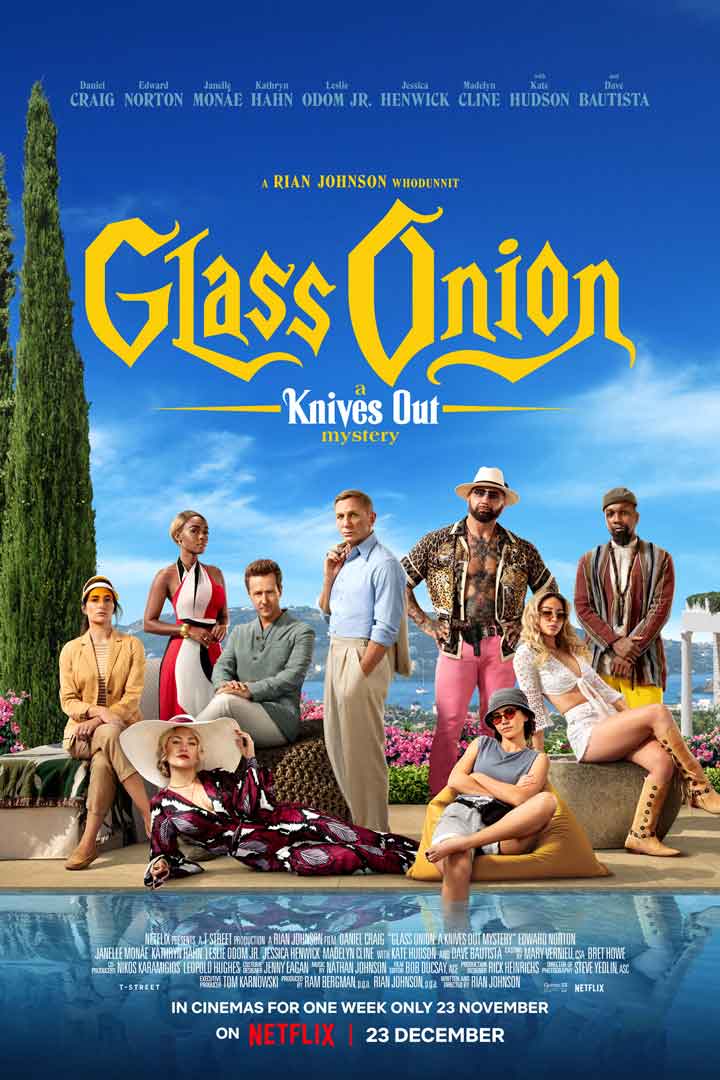

This development to Blades Out — the first of an enormous, extravagant arrangement made with Netflix — lays out the Christie-esque point of reference that Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) is the main repeating component in the series; another case and another cast of characters will show up each time. So however much this is in fact a spin-off, it seems more like the most recent passage in a continuous collection, a particular story that can be delighted in simply in its own specific manner.

This shouldn’t imply that there aren’t shared traits with the first, and as a matter of fact this is a lot of business as usual: a brilliant retread of all that made Blades Out so profoundly fulfilling. There is, by and by, a strange wrongdoing that self-awarely references the class as it goes (the principal film was set in a wrongdoing writer’s home, reflecting the writer’s made up violations; this is set during an end of the week long homicide secret game). There are bodies and blood-splatters. There are curves and misleads, remunerating rehash watchers. There is a last summation and large uncover, in what might be compared to a drawing room.

Be that as it may, everything looks and feels extraordinarily changed, and not simply in the financial plan flexes Netflix can now manage. Where Blades Out was a claustrophobic, fall, New Britain sort of whodunnit — summoning the gothic tension of Detective or the curve mind of Sign — Johnson decides on something else entirely here: a mid year occasion turned out badly, his interpretation of Christie’s A Caribbean Secret, or all the more precisely, Stephen Sondheim’s The Remainder Of Sheila (and Sondheim as a matter of fact procures a short, splendid post mortem gesture in this film).

This time, as well, Blanc is no more “only a detached obsuh-vuh of reality” — he’s a functioning player for the situation. A person recently presented in an out-of-center foundation shot currently comes to the closer view: we find out a little about his own life, his frailties, his proclivity for scrubbing down while wearing a fez, and his broad assortment of cloth neckerchiefs.

In that capacity, he feels more adjusted as a person, both narratively — Johnson is quick to stress his compassion and shrewdness — and comedically, favored with more delightful “Southern hokum”, as Blanc himself humbly puts it. (The people who partook in the “donut openings” of the principal film will take specific help in the manner Craig more than once folds his lips over “support”.) Investing energy in Blanc’s organization stays a solitary joy, and in the event that this is to be a continuous undertaking, as it gives off an impression of being, all there’s possibilities Blanc will be as characterizing a job for Craig as Bond.

He is encircled, normally, by one more eminent assortment of possible killers/murder casualties, Johnson by and by showing his talent for drawing from a shame of acting wealth. (Regardless, it’s excessively great a cast, with standout gifts like Kathryn Hahn given less to do.) You could pick an alternate most loved each time you consider it, yet specific commendation should go to Janelle Monáe, showing flexible parody hacks without precedent for a perplexing job that requires both smashed flummoxes and in the event that looks-could-kill gazes; and Kate Hudson, having a great time as a perpetually dropped fashionista with a propensity for tweeting racial slurs.

They are very entertaining, and with that difference in view from the principal film comes a difference in tone, easing up as the weather conditions lights up. The primary film appeared as though a secret with some comic peppering; this feels more like a satire first, secret second. Once in a while there’s a slight sense that the strangeness might have been gotten control over a bit — there are, according to our observation, nine superstar appearances showered all through, in addition to saucy references to VIP item supports, which starts to feel somewhat overindulgent.

More regularly, however, it offers a sack of onions of tomfoolery, as loud as the best comedies. Critically, as well, the giggles are buttressed — there’s that word once more — by a perfectly developed script, a labyrinth like story that spreads out leisurely and gratifyingly like a riddle box (fitting, given the film starts with a strict riddle box). In the event that the conclusion doesn’t exactly have a similar sting of shock as the main film’s, you will in any case leave feeling especially fulfilled. It is, in a general sense, a legitimate group pleaser, and best knowledgeable about one. To misrepresent Blanc: it simply seems OK. On to the following case!

Leave a Reply